- Home

- Glenn O'Brien

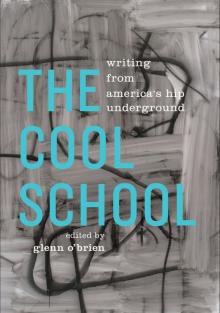

The Cool School

The Cool School Read online

THE

COOL

SCHOOL

writing from america’s hip underground

edited by

glenn o’brien

A Special Publication of

THE LIBRARY OF AMERICA

Introduction, headnotes, and volume compilation copyright © 2013 by

Literary Classics of the United States, Inc., New York, N.Y.

All rights reserved.

No part of the book may be reproduced commercially by offset-lithographic or equivalent copying devices without the permission of the publisher.

Some of the material in this volume is reprinted by permission of the holders of copyright and publication rights. Sources and acknowledgments begin on page 465.

THE LIBRARY OF AMERICA, a nonprofit publisher, is dedicated to publishing, and keeping in print, authoritative editions of America’s best and most significant writing. Each year the Library adds new volumes to its collection of essential works by America’s foremost novelists, poets, essayists, journalists, and statesmen.

If you would like to request a free catalog and find out more about The Library of America, please visit www.loa.org/catalog or send us an e-mail at [email protected] with your name and address. Include your e-mail address if you would like to receive our occasional newsletter with items of interest to readers of classic American literature and exclusive interviews with Library of America authors and editors (we will never share your e-mail address).

Library of Congress Control Number: 2013941522

ISBN 978-1-59853-256-2 (Print)

ISBN 978-1-59853-288-3 (ePub)

Contents

Introduction by Glenn O’Brien

MEZZ MEZZROW/BERNARD WOLFE: If You Can’t Make Money

MILES DAVIS: from Miles: The Autobiography

HENRY MILLER: Soirée in Hollywood

BABS GONZALES: from I Paid My Dues

ART PEPPER: Heroin

HERBERT HUNCKE: Spencer’s Pad

CARL SOLOMON: A Diabolist

NEAL CASSADY: Letter to Jack Kerouac, March 7, 1947 (Kansas City, Mo.)

ANATOLE BROYARD: A Portrait of the Hipster

DELMORE SCHWARTZ: Hamlet, or There Is Something Wrong With Everyone

CHANDLER BROSSARD: from Who Walk in Darkness

TERRY SOUTHERN: You’re Too Hip, Baby

ANNIE ROSS: Twisted

LORD BUCKLEY: The Naz

KING PLEASURE: Parker’s Mood

DIANE DI PRIMA: from Memoirs of a Beatnik

JACK KEROUAC: The Origins of the Beat Generation

JOYCE JOHNSON: from Minor Characters

GREGORY CORSO: Marriage

BOB KAUFMAN: Walking Parker Home

LESTER YOUNG / FRANÇOIS POSTIF: Lesterparis59

NORMAN MAILER: The White Negro

FRANK O’HARA: The Day Lady Died

AMIRI BARAKA (LEROI JONES): The Screamers

ALEXANDER TROCCHI: from Cain’s Book

FRAN LANDESMAN: The Ballad of the Sad Young Men

JOHN CLELLON HOLMES: The Pop Imagination

SEYMOUR KRIM: Making It!

DEL CLOSE: Dictionary of Hip Words and Phrases

LENNY BRUCE: Pills and Shit: The Drug Scene

MORT SAHL: The Billy Graham Rally

BOB DYLAN: from Chronicles: Volume One

JACK SMITH: The Perfect Filmic Appositeness of Maria Montez

WILLIAM S. BURROUGHS: Last Words

ED SANDERS: Siobhan McKenna Group-Grope

RUDOLPH WURLITZER: from Nog

BRION GYSIN: from The Process

ISHMAEL REED: from Mumbo Jumbo

BOBBIE LOUISE HAWKINS: Frenchy and Cuban Pete

RICHARD BRAUTIGAN: The Kool-Aid Wino

ANDY WARHOL: from a: a novel

GERARD MALANGA: Photos of an Artist as a Young Man

NICK TOSCHES: from Dino

HUNTER S. THOMPSON: from Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas

RICHARD MELTZER: Luckies vs. Camels: Who Will Win?

DAVID RATTRAY: How I Became One of the Invisible

IRIS OWENS: from After Claude

LESTER BANGS: How to Succeed in Torture Without Really Trying

RICHARD HELL: Blank Generation

LYNNE TILLMAN: Madame Realism Asks What’s Natural About Painting?

COOKIE MUELLER: Abduction and Rape—Highway 31—1969

GARY INDIANA: Roy Cohn

RICHARD PRINCE: The Velvet Well

GLENN O’BRIEN: Beatnik Executives

EMILY XYZ: Sinatra Walks Out

ERIC BOGOSIAN: America

GEORGE CARLIN: A Modern Man

Sources & Acknowledgments

Introduction

1.

I’m hip.

That means “I know.”

My friend Eric Mitchell says Hip comes from the West African word “hipi” meaning “to open one’s eye.” (Some philologists disagree but Eric is hip.)

If you’re hip your eyes are open, all three of them.

Hip is kind of like being gnostic. How do I know? I don’t know, I just know.

2.

Hipness is a pre-existing condition, something you discover in yourself by yourself.

To be hip is to be an outsider who connects with other outsiders to become insiders of a sort.

To be hip is to belong to an underground, a subculture or counterculture, an elective tribe located within a larger community, outsiders inside. It is detached from the main thing and proud of its detachment. Hip is not always an option but it is always optional.

To be hip is to be Other. (Rimbaud: “I is another.”) We all feel other sometimes and some feel it all the time. The other is the outsider within: the shunned, the excluded, the non-conformist, the escapist, the oddball, the misfit, the square peg, the freak. One of “us” gone rogue, gone haywire, gone wrong trying to get right.

The hipster is either the next step in evolution or the type next destined for extinction.

3.

Cab Calloway defined hep cat as “a guy who knows all the answers.” Thus hep cats date back to Socrates (470–399 B.C.E.), who knew all the questions.

So Socrates was probably the first historical hipster. The first real beatnik might have been Diogenes (412–323 B.C.E.), the philosopher who lived in a barrel in Athens during the time of Plato. When Alexander the Great asked him if he wanted anything, he said “Yes, don’t block my sunshine.” He was a dropout.

4.

The original hipster was an underground figure: an outlaw, an outsider, an outcast, an exile, a heretic, a Bohemian, a misfit, a pariah, a fugitive—a street person, a criminal, a sexual outlaw, a madman. America had known many such.

“So it is no accident that the source of Hip is the Negro for he has been living on the margin between totalitarianism and democracy for two centuries.”—Norman Mailer, “The White Negro”

In the early twentieth century black culture, rooted in jazz with its free sexuality and use of marijuana and other drugs, was an outlaw culture that required an opaque language and a speakeasy limited access to survive.

“And Newark always had a bad reputation, I mean, everybody could pop their fingers. Was hip. Had walks.”—Amiri Baraka

5.

The hipster is identified by language reflecting an alternate set of values—a lingo or slang not understood by the mainstream. It is a language whose meaning may be multileveled and whose surface may be deliberately misleading. Thus, to understand—to catch the deliberate drift—is to dig.

“Dig: Understand, appreciate . . . Often used as interjectory verbal punctuation, to command attention or to break up thoughts. ‘Dig. We were walking down Tenth Avenue, you dig it, and dig! Here comes this cop. So dig, here’s what we did.”—Del Close

Hip language is a living medium. The dictionary of hip is unprintable as it is always mutating faster than fruit flies, too fast for the squares to catch on.

“By the time they catch us we’re not there.”—Ishmael Reed, “Foolology”

To get it you have to have, like Jesus put it, “ears to hear.” Like Antony said, “Lend me your ears.” Like Lord Buckley said, “Knock me your lobes.”

The hipster spoke jive talk. Jive was jazz talk. A 1928 dictionary defined it as “to deceive playfully” (v.), also “empty misleading talk” (n.). It was ironical language copped from blacks and Jews, gays and jazz musicians and junkies, bootleggers and second story men. Jive was an underground, initiatory language existing, the vernacular as survival strategy, a way of speaking in front of the enemy without being understood. It is the language of the marginalized—although sometimes it isn’t simply a way of excluding people outside the group from understanding, but also of bonding and affirming status within the insider/outsider group: converting exclusion into exclusivity. Can you dig it?

6.

“As he was the illegitimate son of the Lost Generation, the hipster was really nowhere.”—Anatole Broyard

In “The White Negro” Norman Mailer explained the hipster as a result of existentialism hitting the melting pot. Mailer’s hipster is a white man who removes himself from the culture into which he was born because of existential dread. Dread from the A-bomb’s threat of mass extinction or the corporate world’s mass identity extinction.

“One is Hip or one is Square . . . one is a rebel or one conforms, one is a frontiersman in the Wild West of American night life, or else a Square cell, trapped in the totalitarian tissues of American society, doomed willy-nilly to conform if one is to succeed.”—Norman Mailer, “The White Negro”

7.

The hipster is cool because he is detached, or semi-detached. He is independent. He is non-invasive and self-contained. A group of hipsters might be called an archipelago.

Cool isn’t something invented recently. It was probably cool in the caves where the original underground cats dwelt. When the tribe was having a war dance, the cool one wasn’t dancing, but he might have been playing a drum in the corner. Syncopated.

Cool cannot be faked. Someone trying to be cool is generally more uncool than somebody who is not trying at all.

Cool is like grace. It can be sold but not bought.

Cool is provisional. Cool wants to think it over and get back to you.

“There is a cool spot on the surface of Venus three hundred degrees cooler than the surrounding area. I have held that spot against all contestants for five hundred thousand years.”—William S. Burroughs

“Nothing gives one person so much advantage over another as to remain always cool and unruffled under all circumstances.”—Thomas Jefferson

8.

“By 1948 it began to take shape. That was a wild vibrating year when a group of us would walk down the street and yell hello and even stop and talk to anybody that gave us a friendly look. The hipsters had eyes.”—Jack Kerouac

“All the people who, like me, had hidden and skulked, writing down what they knew for a small handful of friends . . . waiting with only a slight bitterness for the thing to end, for man’s era to a close in a blaze of radiation—all these would now step forward and say their piece.”—Diane di Prima

As the Beats got exposure, their bohemian enclaves supplied the big city with some excitement, and gave youth somewhere to rebel to. It was hang in the enclave or hit the road—and it was no coincidence that the Genesis of Beat was On the Road. Already the scene was not a place but a trip.

9.

To the latter day hipsters of my baby boom generation hipness was redefined as a kind of religion, a trans-apocalyptic cult that burned cool, that fluoresced around us, threatening to erase official history in a spontaneous rhythmic carnal uprising, a revolution of the mind, an eruption of eros, and enlightenment. It was where we came in.

The whole scene morphed from cool detachment to swirling total immersion, from nihilism to nirvana.

It became a spectrum of otherness: Hippies and Yippies, Panthers and Diggers and Merry Pranksters.

We weren’t Americans anymore. The hipster had become a cosmopolite, an organism that occurs in most parts of the world. The hipster feels at home or not at home everywhere equally.

But finally every hipster is the citizen of himself.

“The hipster has usually been associated with being a number, a hot card, something oddly independent, responsive to whatever circumstance he finds himself in, disaffiliated but sovereign to whatever turf he finds himself wise to.”—Richard Prince

10.

A funny thing happened on the way to nirvana. Handfuls of demonstrators turned into “the armies of the night.” The counterculture grew so large it became a sort of co-culture. The success of the hip changed the trip. It was no longer Route 66 but the Interstate, no longer boxcars but tour jets.

For true believers in rebellion as a conspiracy against fascist control and the status quo, the end of the twentieth century proved a disappointment as the counterculture was absorbed nearly whole by the mechanisms of consumer culture. The radical ideas of the sixties went into business for themselves. It wasn’t only that boundary-breaking genres were co-opted. They were embraced and enthusiastically marketed to such an extent that it was increasingly difficult to maintain a serious posture of opposition. Fashion raided the archives of the underground and began selling a simulacrum of rebellion.

The crazed hippies intent on destroying the system sold like hotcakes. Cool hotcakes. They became product despite themselves, to spite themselves.

11.

But sometimes a simulacrum gives you a taste and you want more. You want the real thing. The appearance of rebellion could still supply a frisson to bored youth who saw the youthful antics of predecessor generations as exciting.

There was little to revolt against except ennui, but that was something.

The young began dressing like pictures they had seen of rebels past, rebels who seemed to be having a wild time that was no longer accessible.

12.

Today if you use the term hipster it’s usually referring to a kind of look. The online urban dictionary actually says “The ‘effortless cool’ urban bohemian look of a hipster is exemplified in Urban Outfitters and American Apparel ads which cater toward the hipster demographic.”

I had noticed the new class hipsters but I didn’t pay them much mind except to admire their fedoras, beards, and tattoos. Looking or simulating interesting may be the first step toward being that way. They certainly looked more interesting than the power-suited yuppies of the eighties, but their focus seemed more about craft beers and artisanal cheese than more profound cultural involvement.

Then I was browsing at a bookstore in Berlin and I came across a book the title of which intrigued me: What Was the Hipster? It had been put together by a bunch of young Brooklynite intellectuals, apparently neither bearded nor tattooed. The book’s premise was that the hipster was a fairly recent phenomenon and that it was over, and in retrospect it wasn’t anything that anyone would have genuinely wanted to be anyway. I found that puzzling as I had always wanted to be a hipster from slightly before the moment that I figured out what a beatnik might be.

I realized that the word had changed meaning while I was dozing in the sun or strolling on a golf course. According to the leader of their panel of experts, Mark Greif: “. . . the contemporary hipster seems to emerge out of a thwarted tradition of youth subcultures, subcultures which had tried to remain independent of consumer culture, alternative to it, and been integrated, humiliated, and destroyed.”

“Oh wow!” I thought, in the words of Maynard G. Krebs, the cat who had me playing bongos when I was twelve. Humiliated and destroyed by consumer culture! Not again! This generation sure went down in flames a lot easier than the hippies and the punks.

13.

; Finally I figured out what these guys were talking about. One of their definitions of this new hipster was “rebel consumer”—“the culture figure of the person, very possibly, who understands consumer purchases within the familiar categories of mass consumption . . . like the right vintage T-shirt, the right jeans, the right foods for that matter—to be a form of art.”

That rang a bell and it sounded like Richard Prince’s fault. I had seen the hip career choice change from rock musician or painter, to DJ or curator. Life had become a matter of selecting among ready-mades. Greif concludes his essay: “The 2009 hipster becomes the name for that person who is a savant at picking up the tiny changes of consumer distinction and who can afford to live in the remaining enclaves where such styles are picked up on the street rather than, or as well as, online.”

I could actually dig that analysis. It took me back to the early nineties when I was asked the definition of Alternative Music, then a principle category in music, and I replied “mainstream.” I had once asked Madonna why her music was categorized as Pop while Elvis Costello’s was Alternative and she said, “Because he’s not good looking.”

14.

The scary thing about this project is that you begin to realize that the underground as we used to know it really doesn’t exist anymore except in our nostalgia for it. Burroughs was always quoting Hassan i Sabbah, the Old Man of the Mountains, the founder of the assassin order, the first terrorist: “Nothing is true. Everything is permitted.”

And never was this more true. Or permitted. Marketing has simply turned the forbidden, the underground, the enemy even, into something marketable. What once made artistic products underground was either censorship or cultural disapproval enforced by the guardians of the marketplace. If a book or a band was too outrageous it wasn’t considered for production. But in the digital age the gatekeepers are out of business.

The Cool School

The Cool School